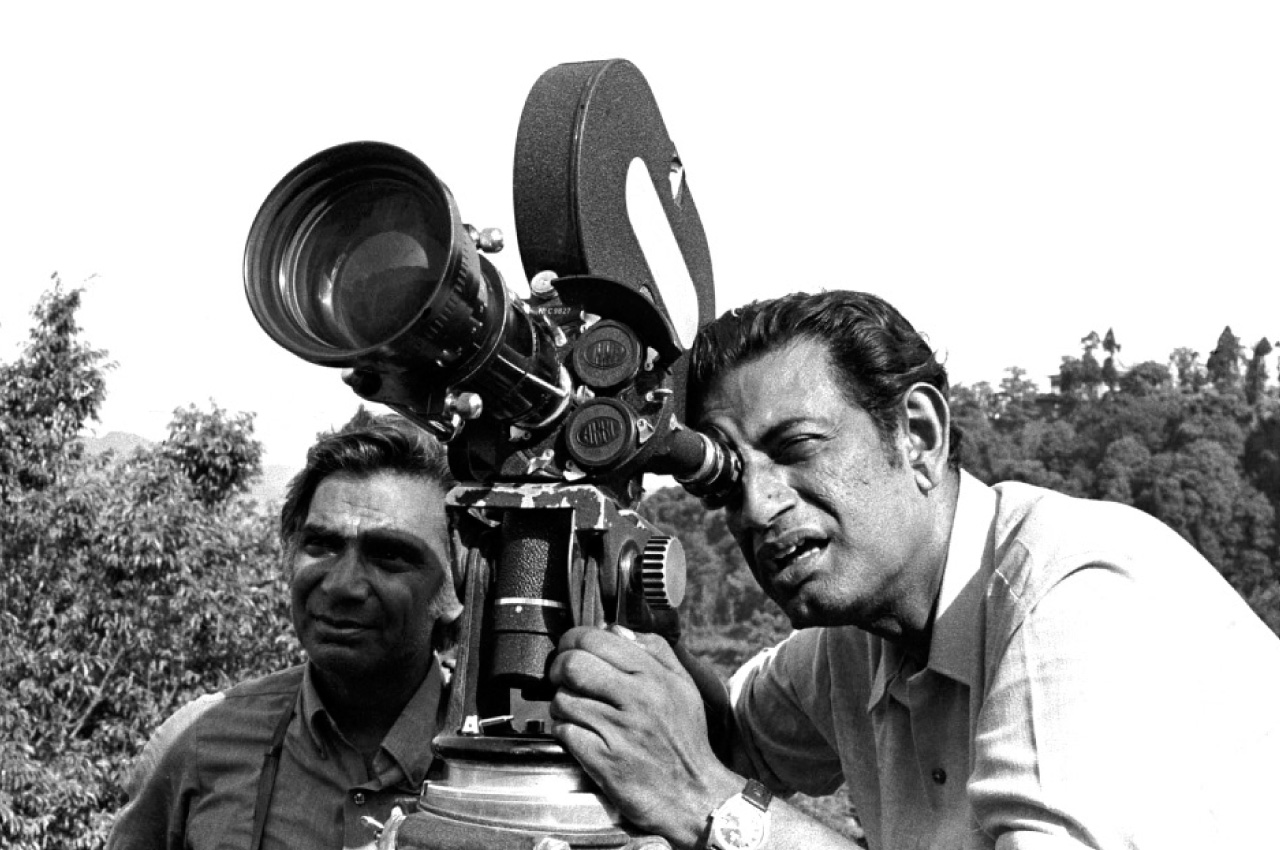

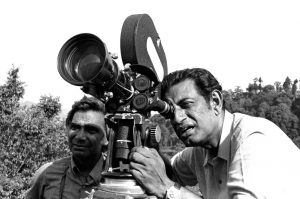

Satyajit Ray was a Bengali motion-picture director, writer, and illustrator who brought the Indian cinema to world recognition with Pather Panchali (1955; The Song of the Road) and its two sequels, known as the Apu Trilogy. As a director Ray was noted for his humanism, his versatility, and his detailed control over his films and their music. He was one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century.

Satyajit Ray was a Bengali motion-picture director, writer, and illustrator who brought the Indian cinema to world recognition with Pather Panchali (1955; The Song of the Road) and its two sequels, known as the Apu Trilogy. As a director Ray was noted for his humanism, his versatility, and his detailed control over his films and their music. He was one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century.

Ray was an only child whose father died in 1923. His grandfather was a writer and illustrator, and his father, Sukumar Ray, was a writer and illustrator of Bengali nonsense verse. Ray grew up in Calcutta and was looked after by his mother. He entered a government school, where he was taught chiefly in Bengali, and then studied at Presidency College, Calcutta’s leading college, where he was taught in English. By the time he graduated in 1940, he was fluent in both languages. In 1940 his mother persuaded him to attend artschool at Santiniketan, Rabindranath Tagore’s rural university northwest of Calcutta. There Ray, whose interests had been exclusively urban and Western-oriented, was exposed to Indian and other Eastern art and gained a deeper appreciation of both Eastern and Western culture, a harmonious combination that is evident in his films.

Returning to Calcutta, Ray in 1943 got a job in a British-owned advertising agency, became its art director within a few years, and also worked for a publishing house as a commercial illustrator, becoming a leading Indian typographer and book-jacket designer. Among the books he illustrated (1944) was the novel Pather Panchali by Bibhuti Bhushan Banarjee, the cinematic possibilities of which began to intrigue him. Ray had long been an avid filmgoer, and his deepening interest in the medium inspired his first attempts to write screenplays and his cofounding (1947) of the Calcutta Film Society. In 1949 Ray was encouraged in his cinematic ambitions by the French director Jean Renoir, who was then in Bengal to shoot The River. The success of Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief (1948), with its downbeat story and its economy of means—location shooting with nonprofessional actors—convinced Ray that he should attempt to film Pather Panchali.

But Ray was unable to raise money from skeptical Bengali producers, who distrusted a first-time director with such unconventional ideas. Shooting could not begin until late 1952, using Ray’s own money, with the rest eventually coming from a grudging West Bengal government. The film took two-and-a-half years to complete, with the crew, most of whom lacked any experience whatsoever in motion pictures, working on an unpaid basis. Pather Panchali was completed in 1955 and turned out to be both a commercial and a tremendous critical success, first in Bengal and then in the West following a major award at the 1956 Cannes International Film Festival. This assured Ray the financial backing he needed to make the other two films of the trilogy: Aparajito (1956; The Unvanquished) andApur Sansar (1959; The World of Apu). Pather Panchali and its sequels tell the story of Apu, the poor son of a Brahman priest, as he grows from childhood to manhood in a setting that shifts from a small village to the city of Calcutta. Western influences impinge more and more on Apu, who, instead of being satisfied to be a rustic priest, conceives troubling ambitions to be a novelist. The conflict between tradition and modernity is the great theme spanning all three films, which in a sense portray the awakening of India in the first half of the 20th century.

Ray never returned to this saga form, his subsequent films becoming more and more concentrated in time, with an emphasis on psychology rather than conventional narrative. He also consciously avoided repeating himself. As a result, his films span an unusually wide gamut of mood, milieu, period, and genre, with comedies, tragedies, romances, musicals, and detective stories treating all classes of Bengali society from the mid-19th to the late 20th century. Most of Ray’s characters are, however, of average ability and talents—unlike the subjects of his documentary films, which include Rabindranath Tagore (1961) and The Inner Eye (1972). It was the inner struggle and corruption of the conscience-stricken person that fascinated Ray; his films primarily concern thought and feeling, rather than action and plot.

Some of Ray’s finest films were based on novels or other works by Rabindranath Tagore, who was the principal creative influence on the director. Among such works, Charulata (1964; The Lonely Wife), a tragic love triangle set within a wealthy, Western-influenced Bengali family in 1879, is perhaps Ray’s most accomplished film. Teen Kanya (1961; “Three Daughters,” English-language title Two Daughters) is a varied trilogy of short films about women, while Ghare Baire (1984; The Home and the World) is a sombre study of Bengal’s first revolutionary movement, set in 1907–08 during the period of British rule.

Ray’s major films about Hindu orthodoxy and feudal values (and their potential clash with modern Western-inspired reforms) includeJalsaghar (1958; The Music Room), an impassioned evocation of a man’s obsession with music; Devi (1960; The Goddess), in which the obsession is with a girl’s divine incarnation; Sadgati (1981; Deliverance), a powerful indictment of caste; and Kanchenjungha (1962), Ray’s first original screenplay and first colour film, a subtle exploration of arranged marriage among wealthy, westernized Bengalis. Shatranj ke Khilari (1977; The Chess Players), Ray’s first film made in the Hindi language, with a comparatively large budget, is an even subtler probing of the impact of the West on India. Set in Lucknow in 1856, just before the Indian Mutiny, it depicts the downfall of the ruler Wajid Ali at the hands of the British with exquisite irony and pathos.

Although humour is evident in almost all of Ray’s films, it is particularly marked in the comedy Parash Pathar (1957; The Philosopher’s Stone) and in the musical Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969; The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha), based on a story by his grandfather. The songs composed by Ray for the latter are among his best-known contributions to Bengali culture.

The rest of Ray’s major work—with the exception of his moving story of the Bengal Famine of 1943–44,Ahsani Sanket (1973; Distant Thunder)—chiefly concerns Calcutta and modern Calcuttans. Aranyer Din Ratri (1970; Days and Nights in the Forest) observes the adventures of four young men trying to escape urban mores on a trip to the country, and failing. Mahanagar (1963; The Big City) and a trilogy of films made in the 1970s—Pratidwandi (1970; The Adversary), Seemabaddha (1971; Company Limited), and Jana Aranya (1975; The Middleman)—examine the struggle for employment of the middle class against a background (from 1970) of revolutionary, Maoist-inspired violence, government repression, and insidious corruption. After a gap in which Ray made Pikoo (1980) and then fell ill with heart disease, he returned to the subject of corruption in society. Ganashatru (1989; An Enemy of the People), an Indianized version of Henrik Ibsen’s play, Shakha Prashakha (1990; Branches of the Tree), and the sublime Agantuk (1991; The Stranger), with their strong male central characters, each represent a facet of Ray’s own personality, defiantly protesting against the intellectual and moral decay of his beloved Bengal.

The motion-picture director also established a parallel career in Bengal as a writer and an illustrator, chiefly for young people. He revived the children’s magazine Sandesh (which his grandfather had started in 1913) and edited it until his death in 1992. Ray was the author of numerous short stories and novellas, and in fact writing, rather than filmmaking, became his main source of income. His stories have been translated and published in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere. Some of Ray’s writings on cinema are collected in Our Films, Their Films (1976). His other works include the memoirYakhana chota chilama (1982; Childhood Days).

The article was originally published in Britannica