Filmmaker was unconcerned with historical accuracy and attempted to explore the human condition in an age before Christianity and the concept of original sin

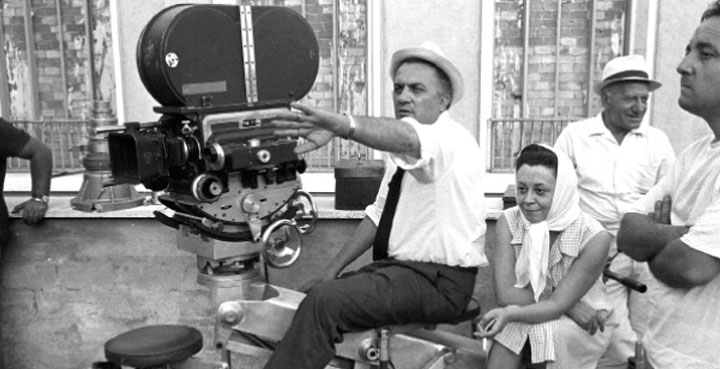

One of the most celebrated and distinctive filmmakers of the period after World War II, Italian film director Federico Fellini is globally known for his distinct filmmaking style. Early in his career he helped inaugurate the Neorealist cinema movement, but he soon developed his own distinctive style of typically autobiographical films that imposed dreamlike or hallucinatory imagery upon ordinary situations and portrayed people at their most bizarre.

After an uneventful provincial childhood during which he developed a talent as a cartoonist, Fellini at age 19 moved to Rome, where he contributed cartoons, gags, and stories to the humour magazine Marc’Aurelio. During World War II, Fellini worked as a scriptwriter for the radio program Cico e Pallina, starring Giulietta Masina, the actress who became Fellini’s wife in 1943 and who went on to star in several of the director’s greatest films during the course of their 50-year marriage.

In 1944, Fellini met director Roberto Rossellini, who engaged him as one of a team of writers who created Roma, città aperta (1945; Open City or Rome, Open City), often cited as the seminal film of the Italian Neorealist movement. Fellini’s contribution to the screenplay earned him his first Oscar nomination.

Fellini quickly became one of Italy’s most successful screenwriters. Although he wrote a number of important scripts for such directors as Pietro Germi (Il cammino della speranza [1950; The Path of Hope]), Alberto Lattuada (Senza pietá [1948; Without Pity]), and Luigi Comencini (Persiane chiuse [1951;Drawn Shutters]), his scripts for Rossellini are most important to the history of the Italian cinema.

These include Paisà (1946; Paisan), perhaps the purest example of Italian Neorealism; Il miracolo (1948; “The Miracle,” an episode of the film L’Amore), a controversial work on the meaning of sainthood; andEuropa ’51 (1952; The Greatest Love), one of the first films in postwar Italy that began to move beyond the documentary realism of the Neorealist period toward an examination of psychological problems and Existentialist themes.

Fellini made his debut as director in collaboration with Lattuada on Luci del varietà (1951; Variety Lights). This was the first in a series of works dealing with provincial life and was followed by Lo sceicco bianco (1951; The White Sheik) and I vitelloni (1953; Spivs or The Young and the Passionate), his first critically and commercially successful work. This film, a bitterly sarcastic look at the idle “mama’s boys” of the provinces, is still considered by some critics to be Fellini’s masterpiece.

Fellini’s next films formed a trilogy that dealt with salvation and the fate of innocence in a cruel and unsentimental world. One of Fellini’s best-known works, the heavily symbolic La strada (1954; “The Road”), starsAnthony Quinn as a cruel, animalistic circus strongman and Masina as the pathetic waif who loves him.

The film was shot on location in the desolate countryside between Viterbo and Abruzzo, with the great empty spaces reflecting the virtual inhumanity of the relationship between the principal characters. Although it was criticized by the left-wing press in Italy, the film was highly praised abroad, winning an Academy Award for best foreign film.

Il bidone (1955; The Swindle), which starred Broderick Crawford in a role intended for Humphrey Bogart, was a rather unpleasant tale of petty swindlers who disguise themselves as priests in order to rob the peasantry. Garnering a second foreign film Oscar for Fellini was the more successful Le notti di Cabiria (1957; The Nights of Cabiria), again starring Masina, this time as a simple, eternally optimistic Roman prostitute. Although not usually considered among Fellini’s greatest works, Le notti de Cabiria (upon which the Broadway musical comedy Sweet Charity was based) remains a critical favourite and one of Fellini’s most immediately likable films.

Fellini’s next film, La dolce vita (1960; “The Sweet Life”), was his first collaboration with Marcello Mastroianni, the actor who would come to represent Fellini’s alter ego in several films throughout the next two decades. The film—for which Fellini had Rome’s main thoroughfare, the Via Veneto, rebuilt as a set—proved to be a panorama of the times, rife with surreal imagery, and a compelling indictment of popular media, decadent intellectuals, and aristocrats.

Immediately hailed as one of the most important films ever made, La dolce vita contributed the wordpaparazzi (unscrupulous yellow-press photographers) to the English language and the adjective “Felliniesque” to the lexicon of film critics.

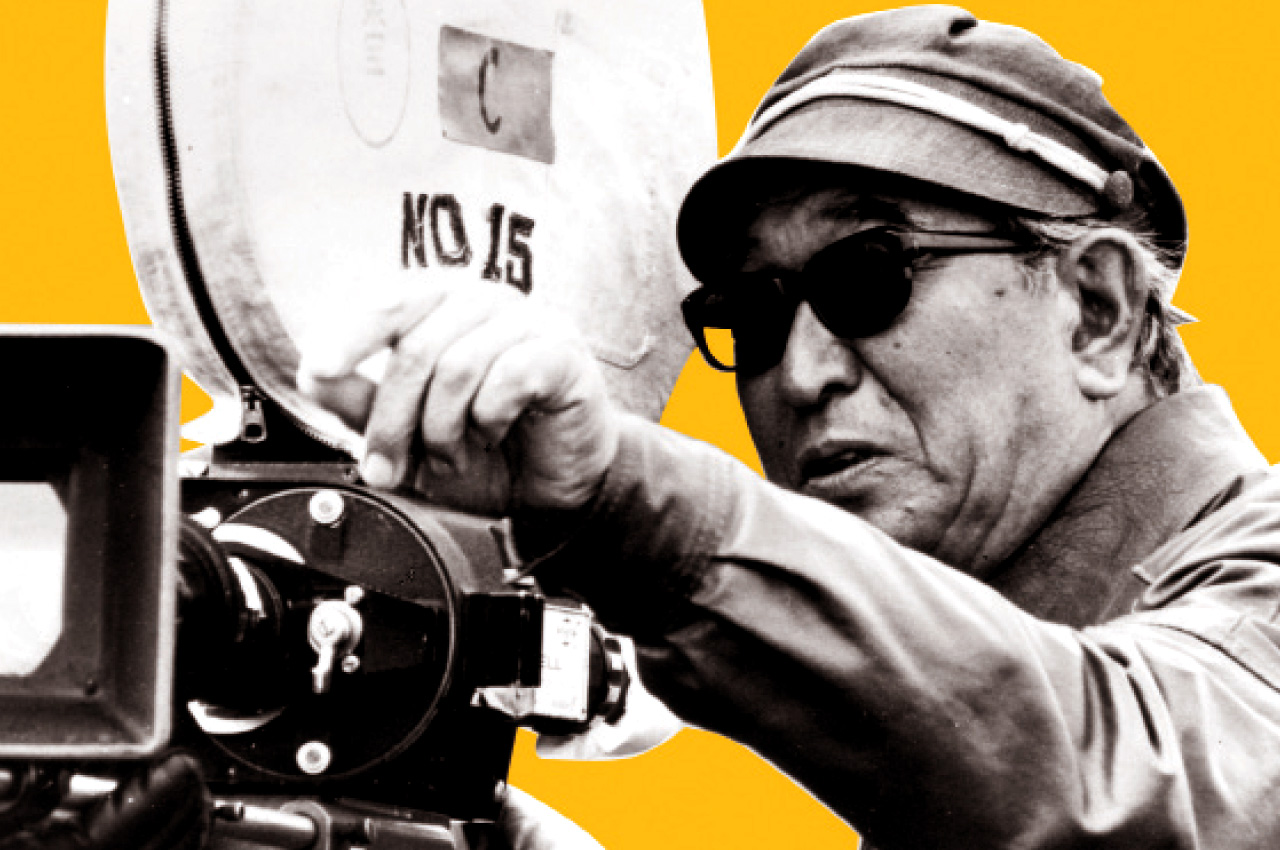

Regarded as a perfect blend of symbolism and realism, Otto e mezzo(1963; 8 1/2), is perhaps Fellini’s most widely praised film and earned the director his third Oscar for best foreign film. Entitled 81/2 for the number of films Fellini had made to that time (seven features and three shorts), the work shows the plight of a famous director (based on Fellini, portrayed by Mastroianni) in creative paralysis.

The high modernist aesthetics of the film became emblematic of the very notion of free, uninhibited artistic creativity, and in 1987 a panel of motion picture scholars from 18 European nations named 8 1/2 the best European film ever made.

In the wake of 8 1/2 Fellini’s name became firmly linked to the vogue of the postwar European art film. He began to deal with the myth of Rome, the cinema, and, especially, the director’s own life and fantasy world, all of which Fellini considered interrelated themes in his works. Fellini, who was unconcerned with historical accuracy, attempted to explore the human condition in an age before Christianity and the concept of original sin.

Many of Fellini’s later films were less successful commercially and encountered critical resistance. During the last years of his life, Fellini produced television commercials for Barilla pasta, Campari Soda, and the Banco di Roma that are regarded as extraordinary lessons in cinematography revealing the director’s deep grasp of popular culture.

He also exhibited his sketches and cartoons, many of which were taken from his private dream notebooks, thus uncovering the source of much of his artistic creativity, the unconscious.

This article was first published on britannica.com