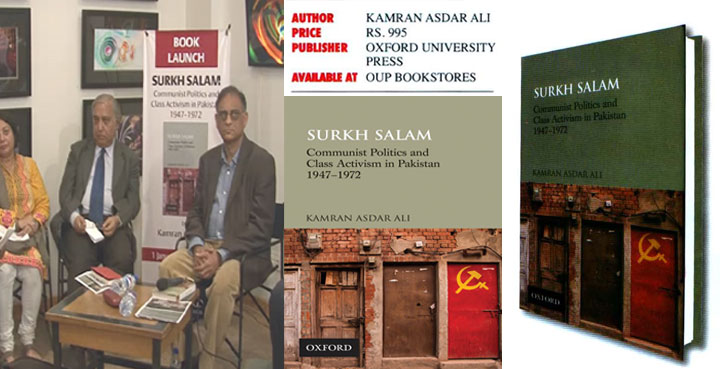

By Kamran Asdar Ali

A complete guide on telling how the Left movement found its place in Pakistan post independence

Not many books describe the existence of the Left in Pakistan, many may get profoundly surprised even on its slight mention, and even if those that do may not guide the reader so comprehensively as the one authored by Kamran Asdar Ali, Associate Professor of Anthropology, and Director of the South Asian Institute at the University of Texas, Austin.

What amazes the reader most is the detailed list of sources and interviews conducted to tap the information.

The book mainly focuses mainly on the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) during its brief period of legal existence (1948-1954), its founding father Sajjad Zaheer, and his misdeeds, exposed in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case, which ruined the party. The CPP never recovered from this fatal blow.

Kamran says, “This book brings back the memory of the 1960s protest movement and other radical confrontations with the state by focussing on communist and working-class history from 1947 to 1972. If the late 1940s are considered the founding moment of communism in the country (along with the independence of Pakistan itself), linked as the period was to the international consolidation of communism in Eastern Europe and the victory of Maoism in China, then the 1960s were surely its zenith, as urban-based working-class and student movements destabilised the status quo. Hence, the book begins by critically engaging with the history of the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) during its brief period of legal existence (1948-1954) and ends in the early 1970s by discussing the social and historical process that led to the substantive decline of labour and class-based politics and the concurrent forceful emergence of a politics increasingly shaped by issues of ethnic, religious and sectarian differences that mark contemporary Pakistan.”

Kamran works hard to trace the CPP’s roots to its parent, the Communist Party of India (CPI), and the Adhikari thesis, which sought to build a bridge with the Muslim League, now committed to Pakistan.

“This book is based on oral testimonies, ethnographic fieldwork and archival research. In Pakistan, in addition to interviewing Communist Party members, labour activists, government officials and student leaders, I conducted archival research in public and private collections, read newspaper reports and worked with memoirs of activists, literary figures and communist leaders (in English and Urdu). For this purpose, I also did research at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., where I looked at the United States State Department dispatches from Pakistan on its labour and communist movement (including some declassified CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] papers) from the 1950s and 1960s. I spent two extended periods in the Netherlands at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) which has a special collection on Pakistan labour politics and its linkage with international labour organisations such as the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU). Other important sources on the Communist Party were the police reports that I miraculously found in a private collection in Pakistan and the political reports sent by British diplomats to the United Kingdom which are housed at the National Archives in London. I also relied on old volumes of Soviet publications, scholarly articles and conference reports (especially pertaining to cultural policies) along with Chinese periodicals that I found through the interlibrary loan system while at the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin. Finally, again closer to my academic home, I found copies of the Communist Party of India’s English language publication, The Communist, for the years 1940-1948 at the Harry Ranson Centre at the University of Texas, Austin,” Kamran articulates.

The book is a must read for someone willing to discover thus unknown Leftist facet of Pakistan!