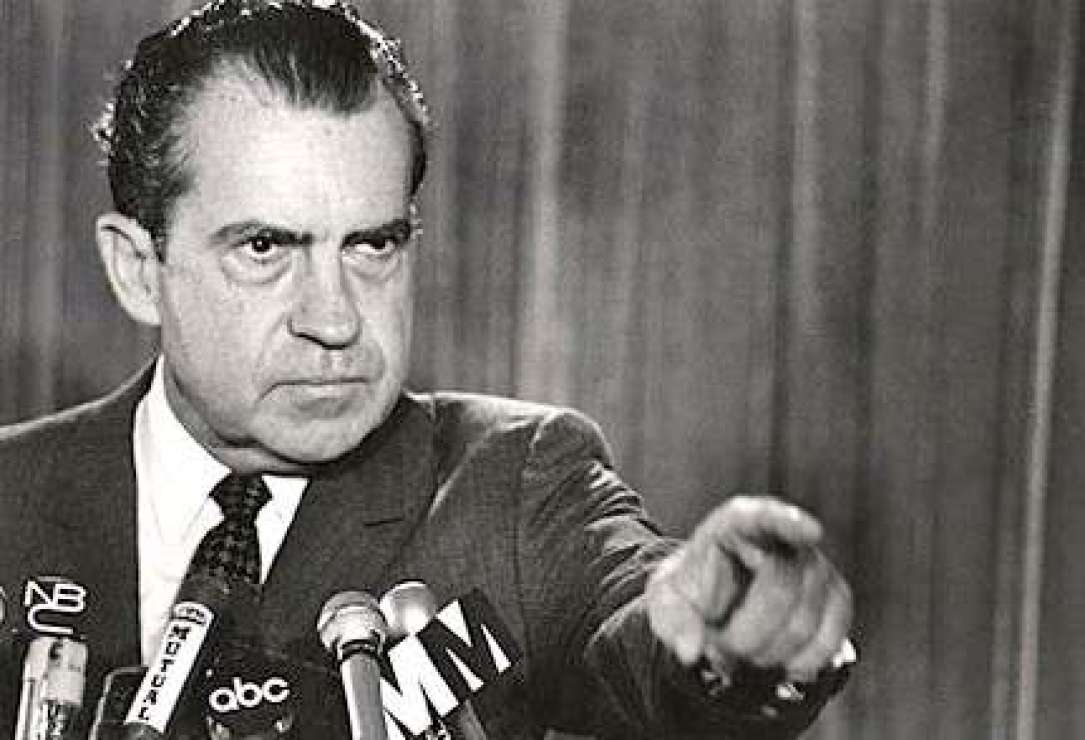

New Delhi: In February 1971, President Richard Nixon had begun taping conversations and telephone calls in secret, in several locations, including the Oval Office, his office in the Old Executive Office Building, the Cabinet Room, and Camp David. Richard Nixon wanted an accurate record of his presidency for his own use in preparing his accounts and other writing projects that he might undertake after his term of office was over.

The taping system initiated operating in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room on February 16, 1971. Two months later on April 6, the president’s office in the Old Executive Office Building and his telephones in both this office and the Oval Office, and the telephone in the Lincoln Sitting Room in the Residence, too were included in the system. Over a year later, on May 18, 1972, the president’s office and two telephones in Aspen Lodge at Camp David were also added. As per the design, only a few individuals, apart from President Nixon and H. R. Haldeman, knew of the existence of the taping system: Alexander P. Butterfield, Haldeman’s assistant Lawrence Higby, and the Secret Service technicians who had installed it.

Since when the taping system was first seriously discussed, President Nixon asserted that the recordings were to be for his use, and perhaps for Haldeman’s use, only. Nobody else was to listen to those tapes; as few people as possible were to know of their existences because Nixon’s assistants were running a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage on behalf of Nixon’s reelection effort. Later, Stephen B. Bull, who replaced Butterfield in February 1973, would come to know about this too. No one else on the White House staff or anywhere else, or any of the other people made famous during the President Nixon’s tenor, knew of the existence of the taping system until John Daniel Ehrlichman who was the counsel and Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs learned of it during Watergate discussions in March 1973.

The Arrest

The Watergate scandal arose on June 17, 1972, a security guard saw five men dressed in black breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office complex in Washington, DC. When the five men were arrested by police, it was discovered that one of them was connected with the Committee for the Re-Election of the President, a fundraising organization set up by US President Richard Nixon. The remaining four burglars had Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) contacts. They included E. Howard Hunt, a retired CIA operations officer who had played a leading role in the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. It was eventually discovered that the burglary had been authorized by President Nixon himself, as part of a broader program to sabotage his political opponents.

This was not an ordinary robbery: The burglars were connected to President Richard Nixon’s reappointment campaign and had been held wiretapping phones and thieving documents. Nixon took aggressive steps to cover up the offense afterward. In August, Nixon gave a speech in which he affirmed that the White House staff was not involved in the robbery. Most voters believed him, and in November, the very same year the president was reelected. It later came to the notice that Richard Nixon was not saying the truth; he said all that to win elections and wanted to get reelected. A few days after the break-in, Richard Nixon had arranged thousands of dollars in to give as the bung to the burglars so that they do not reveal the involvement of Nixon. Then, Nixon and his assistants made a plan and decided to inform the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to hamper the FBI’s investigation of the crime. This was a more serious crime than the break-in: It was another misuse of presidential power and a thoughtful hindrance to justice. Later in 1974 August, once his role in the conspiracy was exposed, he resigned.

A few years ago a Freedom of Information Act request was filed by Judicial Watch, a conservative legal regulator, who petitioned to have the document released. The release was approved by a judge in early 2016 and was completed in July.

Role of the CIA

Despite numerous bargains throughout, the document gives the fullest public account of the CIA’s role in the Watergate scandal. It contains the information that exposes one of the men who was arrested in the early hours of June 17, 1972. The man, Eugenio R. Martinez, had been before identified as an “informant” of the CIA. But the newly released document refers to Martinez as an agent —an individual who is actively recruited and trained by a CIA officer acting as a handler. It also states that Martinez was on the payroll of the agency at the time of his arrest, making approximately $600 per month in today’s dollars working for the CIA. Additionally, Martinez, a Cuban who had participated in the Bay of Pigs invasion, retained his contacts with the CIA and kept the agency updated about the burglary, his arrest, and the ensuing criminal investigation.

Frank Sturgis was arrested by police at the Democratic Party headquarters on the sixth floor of Watergate. He was found with four other men, wearing rubber surgical gloves, unarmed, and carrying extensive photographic equipment and electronic surveillance devices. He was officially charged with attempted burglary and attempted an interception of telephone and other conversations. Sturgis was also a part of the Miami Cuban exile community and involved in various “adventures” relating to Cuba which were organized and financed by the CIA. He testified that he had given information, directly and indirectly, to federal government officials, who, he believed, were acting for the CIA. He further testified, however, that at no time did he engage in any activity having to do with the assassination of President Kennedy, on behalf of the CIA or otherwise. He was a member of Operation 40.

His FBI file is 75,253 pages – four times as long as the FBI files on Watergate and almost twice as long as the combined Watergate and JFK Assassination file. Operation 40 was a CIA-sponsored hit squad of the 1960s, composed mostly of Cubans. It was active in the United States and the Caribbean (including Cuba), Central America, and Mexico. It had 86 employees in 1961, of which 37 were trained as case officers. Members of Operation 40 took part in the April 1961, Bay of Pigs Invasion directed in contradiction of the government of Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro.

Role of the press

Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were informed by a family attorney stated that former Federal Bureau of Investigation Associate Director Mark Felt was Deep Throat. According to the reporters, Deep Throat was a key source of information behind a series of articles on a scandal which played a leading role in introducing the misdeeds of the Nixon administration to the public. The scandal would ultimately lead to the resignation of President Nixon as well as prison terms for White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, G. Gordon Liddy, Egil Krogh, White House Counsels Charles Colson, former United States Attorney General John N. Mitchell, John Dean, and presidential adviser John Ehrlichman. He told them that former CIA agent and Nixon staff member Howard Hunt was involved in the Watergate scandal.

Judith Hoback Miller, the woman who was involved in the Watergate scandal in 1972 during the presidency of Richard Nixon. She served as the bookkeeper for the Committee to Re-elect the President, also known as CREEP. She was one of the few people that would talk openly with Woodward and Bernstein, and allowed them to come to her home, although she has stated she was “pretty nervous and scared” and was also “frustrated that the truth wasn’t coming out”. She had the details of the money and who controlled it and who got the money. She had already notified the FBI and felt they were not handling the situation properly. She revealed to them that documents had been destroyed that contained information about financial mishandling and some of the committee members including G. Gordon Liddy and Jeb Stuart Magruder were receiving payouts from a secret fund.

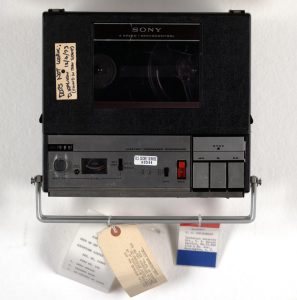

In the late 1980s, a conference was conducted at Hofstra University, where one session was dedicated for the Nixon papers and tapes. The chief speaker was James Hastings, who was the head of the office in the National Archives at that time had the custody of Nixon’s White House tapes. James Hasting had described the tapes—their poor sound quality, their four thousand-hour running time, the twenty-seven thousand-page finding the help that the archivists have prepared in order to describe them to researchers. Few historians in the audience were screaming and waving their hands, as if to say, “No, we don’t want them—it’s too much work,” according to H. R. Haldeman who was among the audience.

The National Archives now owns the tapes and has tried several times to pull through the missing minutes’ recordings—most recently in 2003—but without any lead. The tapes are now conserved in a climate-controlled treasure house in case a future technological development allows for restoration of the missing audio. The White House tapes are available in the form of transcripts as well as audios are also available online. Corporate security expert Phil Mellinger took on a project to restore handwritten notes of various other staff members who were present when Nixon was the President, describing the missing 18½ minutes, though that effort also failed to produce any new information. He tried initiating many social reforms, like public healthcare and he founded the EPA. Richard Nixon broke the law and effectively created the current atmosphere of public distrust of the government. He founded the EPA. Eventually, the White House tapes must shape any valuation of Nixon’s impact and legacy.

In 1974, President Gerald Ford pardoned his predecessor for his involvement in the Watergate scandal. He decided to give Richard Nixon a full pardon for all offenses against the United States in order to put the tragic and disruptive scandal behind all concerned parties involved. Ford justified this decision by claiming that a long, drawn-out trial would only have further polarized the public. The White House tapes not only ended Richard Nixon’s presidency but it also worked as a generation’s cynicism about political leaders.