By Alka Gurha

The story unfolded like a fairy tale. But with a twist. This time the protagonist was not a princess but a young boy. Oblivious of his good looks, the boy earned his living by selling tea, fruit and vegetables at a Sunday bazaar. He had no phone and did not know how to read or write. And yet, he dreamt of helping his poor parents. One day a fairy clicked his picture and posted it on Instagram. The picture captured the imagination of the world. After a makeover, the steaming hot chaiwala morphed into a super cool model. He appeared on television, graced magazine covers, bagged modeling contracts and walked the ramp. Dizzying, isn’t it?

The story unfolded like a fairy tale. But with a twist. This time the protagonist was not a princess but a young boy. Oblivious of his good looks, the boy earned his living by selling tea, fruit and vegetables at a Sunday bazaar. He had no phone and did not know how to read or write. And yet, he dreamt of helping his poor parents. One day a fairy clicked his picture and posted it on Instagram. The picture captured the imagination of the world. After a makeover, the steaming hot chaiwala morphed into a super cool model. He appeared on television, graced magazine covers, bagged modeling contracts and walked the ramp. Dizzying, isn’t it?

Welcome to a world where one picture holds the potential to change the story.

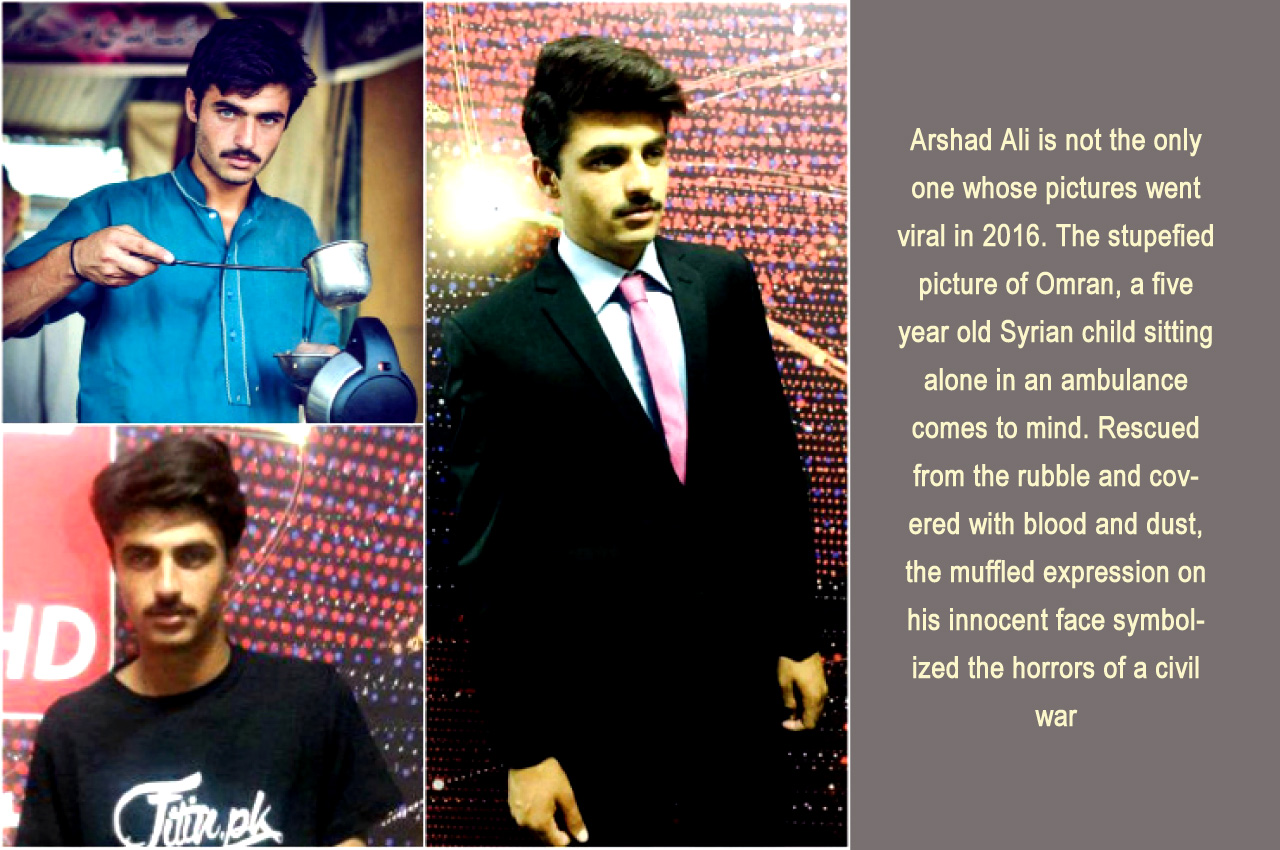

This is what happened to eighteen year old Arshad Ali Khan, an ethnic Pashtun in neighboring Pakistan. His picture was clicked by Jiah Ali, a photo journalist in Islamabad. The caption of Arshad’s picture pouring tea read, “Meet the steamin’ hot ‘chai wala’ from Islamabad (Pakistan), who’s going viral as we speak.”

When I saw this picture on Twitter, it was already shared thousands of times, including Indian social media. At a time when India and Pakistan were divided by terrorism, a random picture had united us, albeit for a few days. “A chai wala from Pakistan is now famous on Indian social media. This is truly aMan kee aasha,” someone chirped.

Arshad, however, was unfazed. “I came to know this morning that I am very good looking. All these people are coming and taking pictures and videos of me,” he said. When asked how he planned to spend the new found money, he said, “I need money to help my family. I am not an educated person and cannot claim that I will become a doctor or a judge.” From what I read, Arshad was amused by the hordes of girls who flocked his tea stall to click pictures.

Obliged by social media, the smitten girls wanted a slice of his fame. And suddenly there was some talk about reverse objectification. For once, it was the girls who were lusting after a good looking boy. To my mind, the objectification charge was silly. Meaningless actually. After all, the camera was simply a catalyst in a win-win situation for both – the muse as well as the modeling firms.

But wait. Arshad Ali is not the only one whose pictures went viral in 2016. The stupefied picture of Omran, a five year old Syrian child sitting alone in an ambulance comes to mind. Rescued from the rubble and covered with blood and dust, the muffled expression on his innocent face symbolized the horrors of a civil war. Likewise, the haunting picture of Aylan Kurdi, a drowned toddler drew our attention towards the plight of Syrian refugees.

To say that an image going viral is an exclusive preserve of social media is perhaps erroneous. Far away from Instagram and way before Twitter, we witnessed a similar trend. Remember the 1984-85 portrait of the Afghan Girl whose green piercing eyes shook our soul? The face, they say is a picture of the mind with the eyes as its interpreter. Perhaps it was those intense eyes – a tapestry of tragedy and pools of grief.

The Afghan Girl went on to become the most memorable cover for the National Geographic magazine. The picture was such a rage that it was likened to Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of Mona Lisa. Most of us didn’t know her name, and yet, the girl attracted our compassion. Come to think of it, her image was etched in our memory without the re-tweets, likes or shares.

For positive tales like Arshad, social media is indeed a fairy Godmother. I don’t know if what began as fairy tale will have a fairy tale ending but what I do know is that the only thing shorter than public memory is public interest. Overnight fame can provide a fillip to any muse or any cause, but it does little to change stories. It is likely that Arshad will be forgotten like Omran. Or Aylan Kurdi. Or Sharbat Gula.

What exactly are we doing for other Omrans being rescued from the rubble? Why, even as I write six children have been slaughtered and dozens injured in a barbaric bombing in a Syrian nursery school. Is our heart bleeding for the Afghan Girl, Sharbat Gula who was arrested in Pakistan for forging national identity card? She’s now a 45 year old widow who wasn’t a registered refugee even though her young face was their symbol.

Coming back to the dreamy eyed Chaiwala, we love his story, don’t we? In fact we love fairy tales – not because they tell tales about monsters but because they tell us that monsters can be overcome. That there is hope. Compassion. But the truth is that social media is fickle, and news ephemeral. And yet, if viral images help a cause or a muse, it is a welcome part of digital times. I’m ready with my likes. And shares.