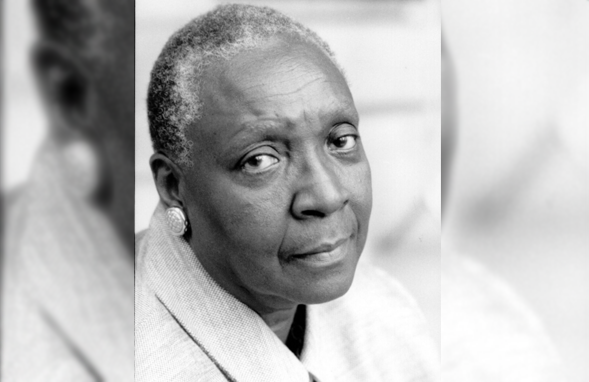

Writer of Africa’s first epic novel, Maryse Condé is one of the most masterly writers from the Caribbean and has written viscerally on the ‘ravages of colonialism and post-colonial chaos in language’ and on black women’s trials and tribulations

In the first year of seventy when the Nobel Literature Prize was suspended due to the unsettling #MeToo scandal that rocked the Swedish institution, Maryse Condé won the alternative to the Nobel Literature Prize, the New Academy Prize, for her sweeping African historical fiction. Condé, born in 1937, is a French writer from the overseas Francophone Caribbean country of Guadeloupe.

Condé’s fiction pays homage to African history, and is a sweeping historical rendition of the pre-colonial and modern African continent. Her novel Segu is a rendition of the royal family of Dousika, a chief of Monzón Diara, in the late 18th c kingdom of Segu which was spread over the present-day west African country of Mali. Segu is considered to be the first epic fiction from Africa. It represents that transition period in African history when it was being ripped apart by European conquerors from the West and dominated over by radical Islamic jihadis from the East. Islam and Christianity are presented in an opposition to the pagan and earthy religions of the indigenous tribal traditions, and are subtly accused of destroying such cultures in more ways than one. Christianity is represented as a mere façade for the slave-trade, and Islam is portrayed as a powerful fundamentalist force, that which subsequently spread to much of West Africa in the 19th century. Moreover, Segu encapsulates the sea-change in all aspects of the pre-colonial and pre-Islamic west African life – the metamorphosis from an independent and vital aboriginal existence to that of exploitation and subversion, where the traditional modes of life were destroyed and lie lifeless and usurped.

Moi, Tituba, Sorciere…Noire de Salem, also known as I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem, won the French Grand Prix award for women’s literature in 1986, and is based on the tale of real-life Tituba, a biracial African slave woman living in the 17th century Barbados and New England. Tituba was accused of witchcraft, and was arrested by the Puritans in the Salem Witch Trials. Condé herself does not refer to this novel as historical, saying that she “invented” the “obscure and forgotten” Tituba for various purposes. The novel captures, more than Tituba’s life journey, the Puritanism and life in 17th century New England from a black person’s and woman’s perspective: ‘Writing Tituba was an opportunity to express my feelings about present-day America. I wanted to imply that in terms of narrow-mindedness, hypocrisy, and racism little has changed since the days of the Puritans.” This pushed her to retrieve that forgotten history of racism that implicated Tituba.

Condé has written about black women in her other works, such as in Pension les Alizes, whose West-Indian protagonist Emma embodies the paradox that, “even when they are very intelligent, the way that most black women can succeed is with their bodies, through their figures. For me, Emma was an exemplification of that dilemma…she came to study medicine…and lived with several German men…[and yet] she was kept a woman…”. It is a rendition of an African woman living in the West trapped in her exotic womanhood. In her works Condé delves into the intertwined web of racism, sexism and classism and confronts this form of intersectional oppression by representing the lived reality of these suffering and prosecuted women.

Author of more than 20 novels, also including Desirada and Crossing the Mangrove, Condé is a grand storyteller whose contributions are to her African heritage and to world literature are immense. It is a form of poetic irony that Maryse Condé, who has confronted women’s exploitation in her works, won the prize this year. She creates a world wherein, according to the chair of judges Ann Pålsson, “the dead live in her stories closely to the living in a … world where gender, race and class are constantly turned over in new constellations.” A world which continues to exist in all its virulent forms to this day.