By Shantanu Srivastava

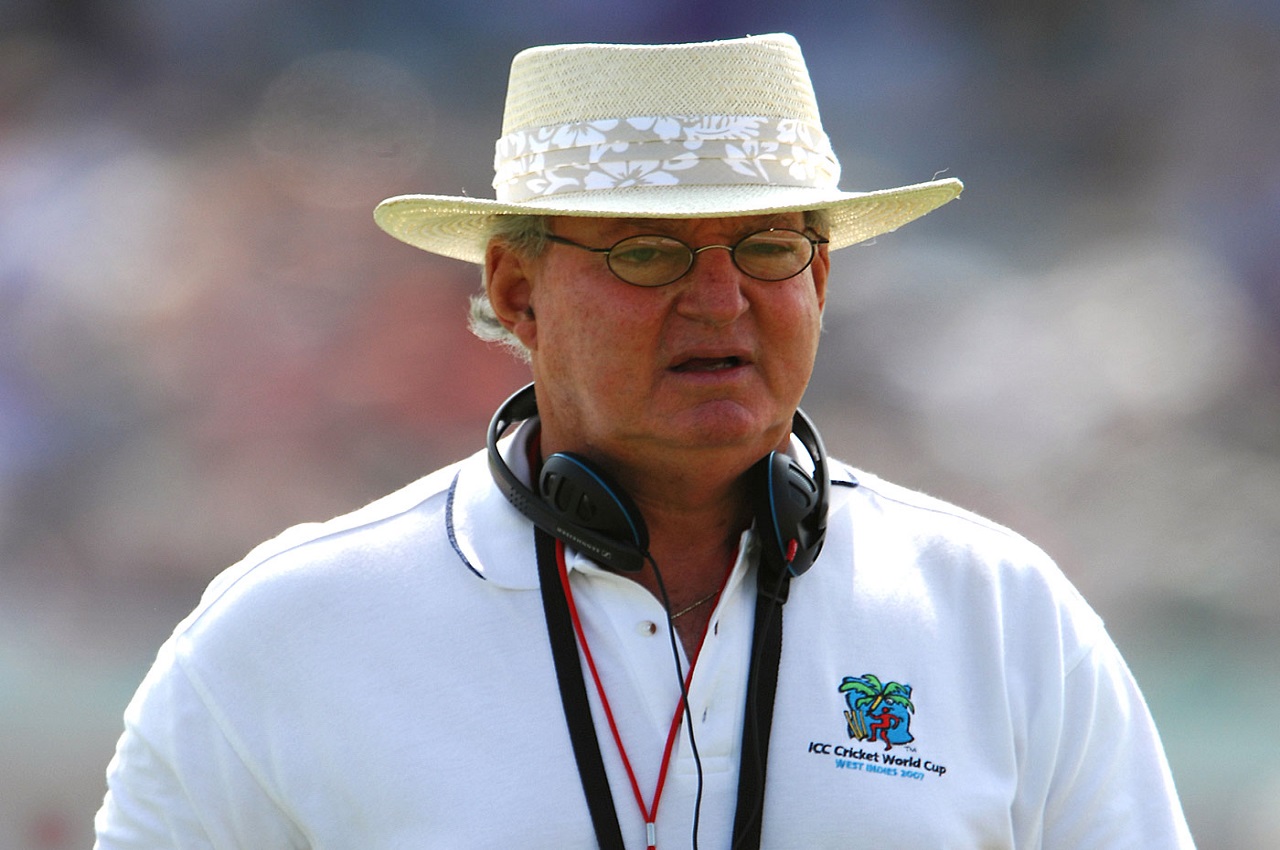

Tony Cozier

What is it about voices that make us fall in love with them? How does the slightest of inflections, lilt and modulation produce the most gigantic of effects on human psyche, enough to send a chill down your spine, enough to set your pulse racing, enough to move you? If you haven’t heard Víctor Hugo Morales describe Diego Maradona’s Goal of the Century in the 1986 World Cup quarter-final between Argentina and England, chances are that may not get through this piece without battling the urge to reach for the dustbin. Here’s a tip: Use the Internet. And thank me later. And once you are done listening to the unabashed, naked rendition of raw passion and abject bewilderment, take a step back and think, would Maradona’s defining run through the English defence be the same without Morales calling him “Barrilete cósmico” (cosmic kite)?

A confession: I never met Tony Cozier. There would hence be no mollycoddling of the departed soul, or for that matter, odious comparisons of him – benevolent gentlemen he was without doubt- with my late grandfather. What really bothers me is the fact that Cozier’s demise is the brutal snipping of the umbilical cord between modern robotics and commentary’s golden age, if ever there was one. As a Test match aficionado, this author particularly drooled over “a marvelloush morning in Melbourne.” Richie Benaud the commentator emphatically overwhelmed Richie Benaud the cricketer, though the latter didn’t too badly on the cricket field, as his three Test tons and 248 Test wickets amply suggest. Every four years, the winter vacations would mean setting early morning alarms and waking up to “marvelloush” mornings in Melbourne.

With the newspaper vendor, the milkman and the first rays of the sun, Benaud would enter our households and conscience on chilly mornings with silken voice and pauses judged as precisely as a copybook leave off the front foot. Then there was Tony. Not Cozier, but Grieg. Indian cricket fans would remember April 1998 with particular pride. As Sachin Tendulkar went about carving knocks for ages, Grieg set about creating a masterpiece of his own. “Whadda Playyaa… what a wonderful little player,” he shrieked in Sharjah, and we believed. “He’s playing for victory…Sachin Tendulkar is playing for victory,” he told us. We knew he was dead right. Both Grieg and Benaud had the enviable positions of authority in the sense that they had represented their countries at the highest level. We knew that they knew what they were talking about. We knew it was a perfect forward defensive because Grieg said so, or the off-drive lacked grace because, you know, Benaud thought so. They were our coaching manuals, our institutions. And we trusted them to light up a dull day of Test cricket with their wit and insights. And then there was Cozier. Winston Anthony Lloyd Cozier. How could you be named Winston Anthony Lloyd Cozier and not Tony Cozier? The avuncular Cozier. The convivial Cozier. The erudite Cozier.

The velvet-voiced Cozier. Even his name had the obvious coziness, and his voice backed it to perfection. Having witnessed both, the dizzying heights that the legendary West Indian teams scaled and the deplorable lows they gradually slipped to, Cozier had the vantage view of the vibrant Caribbean panorama. In more ways than one, he was the outsider. A white in the West Indies (pardon the unintended racism), a diction devoid of frequent references to ‘maan’ (pardon the not-so-inadvertent generalisation), and no experience of competitive cricket beyond club-level meant Cozier had no business being in the cozy club of commentators, much less being the best of the lot. Yet, he not only belonged there, he pretty much ruled the stage. Coming from a land -he was a Bajan- that produced men of such enviable pedigree as Sir Garfield Sobers, Clyde Walcott, Sir Everton Weeks, Gordon Greenidge, among others, it was no coincidence that he liked cricket. That his father ran a newspaper obviously did help, but the thrust needed to launch a career that spanned over 50 years came from the deep love he had for what was then a gentlemen’s game. His was a voice of command. When he lamented the demise of Caribbean spirit in their cricket, we felt his pain. His unequivocal criticism of West Indies Cricket Board over the way it ran cricket caused an irreparable damage in their relationship but Cozier couldn’t careless. He wasn’t a charlatan masquerading as commentator.

Vic Marks of The Guardian calls Cozier’s work ethics an “education.” “To watch Tony at work at a Test match was an education. He would glide between the TV commentary box to the (much smaller) radio box, then back to the press room where he would construct a couple of pieces for the Nation newspaper of Barbados, then perhaps another for the Independent in the UK. It seemed such an effortless process, albeit without a minute wasted,” Marks wrote in his obit. How many of modern-day motormouths can claim to possess such drive? And just how many would have the gall to bypass the gobbledygook, ignore the obvious, chuck the chicanery and care for the unsuspecting fan? How many would follow their conscience and risk their job, as a certain Harsha Bhogle famously found out? In an age where cricketers and commentators are (readily) reduced to walking billboards, Cozier was cricket’s last link with objectivity and innocence. He spoke for the much-maligned spirit of the game. He spoke for me and you – the fan. PS: “When I am nothing more than bones or dust, someone will listen to this goal,” said Morales of his immortal airtime, some 25 years after capturing world’s imagination.