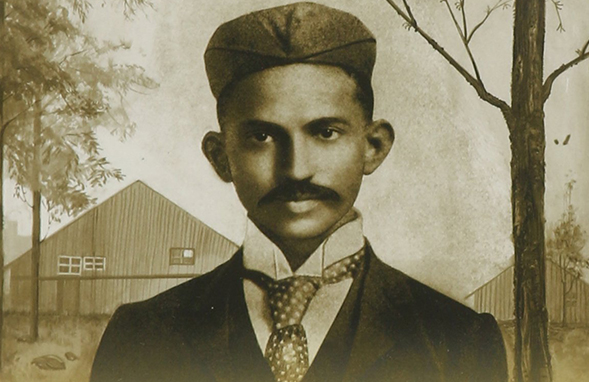

Gandhi in South Africa

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, or Mahatma Gandhi, as he came to be revered later, immeasurably contributed to the emergence of India as an independent nation. Gandhi provided an alternative vision and strategy for attaining independence that became the prevailing discourse of the nationalist movement. Gandhi’s novel political ideology was, according to Judith Brown, “appealed to few wholly, but to many partially”, as everyone could find in it something to identify with. The time which Gandhi spent in South Africa was vital for the evolution of his vision and ideology. Gandhi’s twenty-one year stay in South Africa gave him a world outlook and an internal strength to develop and experiment with the non-violent techniques of struggle. He went there as a lawyer in search of livelihood and returned as Mahatma Gandhi. As Ramchandra Guha succinctly remarks, Gandhi “worked in three different countries (Britain, South Africa and India), as anti-colonial agitator, social reformer, religious thinker and prophet, he brought to the most violent of centuries a form of protest that was based on non-violence”.

As India, this year, celebrates his 150th birth anniversary, we as nation’s thinkers should ponder over his immense contributions towards the making of an independent India. In this context, it wouldn’t be amiss to deliberate on his almost two decades’ stint in South Africa. South Africa shaped Gandhi from a floundering, shy, uncertain and hesitant lawyer, into a confident, effective and an assured person and a social activist. And in-turn, he deeply impacted the history of South Africa, influencing native leaders to forge a struggle and agitation against the deeply entrenched racism, by adopting and adapting the strategies devised by Gandhi. His journey from being Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to a Mahatma was very definitely rooted in South Africa.

Gandhi was born on 2nd October, 1869, in a bania family of a small coastal town of Porbandar in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat. Gandhi was brought up in a deeply religious, though, eclectic environment, in which religious thinkers belonging to different sects and communities were welcomed. In an age where for the conservative bania community social distance with other communities was the norm, Gandhi’s family was open-minded. Mohandas’s mother, Putlibai, introduced him to the splendors and mysteries of faith, and inspired him to be religious but not dogmatic. Gandhi’s school days were unremarkable and he showed average proclivity towards academic subjects. Fortunately, his results in matriculation were good and he could enroll for a BA in a local college. However, Gandhi did not complete the course as he had the better option of going to London for a degree in law. In spite of immense social and financial difficulties, Mohandas proceeded to London in September 1888 for further studies. London was an eye-opening experience for Gandhi, where the seeds of inter-faith connectedness were sown. Gandhi began reading Christian texts, but the Sermon On the Mount went straight to his heart. Comparing it to the Gita, he concluded that both taught that “renunciation was the highest form of religion”. Henry Salt inspired and convinced Gandhi about the virtues of vegetarianism and the rights of animals. It was in London that Gandhi tried his hand at writing and got his article published for the first time in a magazine. He learnt here to relate to different people belonging to different races, religions and interact with them closely. On 10th June 1991 after passing the law examination, Mohandas Gandhi was formally called to the Bar. Gandhi arrived in Bombay in July 1991, as Barrister-at-Law. Gandhi’s stint at practicing law in Bombay High Court was however not successful and left him with a deep feeling of dissatisfaction. And when an opportunity opened in South Africa, Gandhi did not hesitate to avail it. A well-off Muslim merchant based in Natal, Dada Abdulla, needed a London trained lawyer who was fluent in both English and Gujarati. Mohandas fitted the bill perfectly. Gandhi sailed from Bombay to Durban on 24 April 1893.

Two struggles shaped South Africa of that day. One was that between the two white communities – the British and the Afrikaners, who are largely of Dutch origin – for political control. The other was between the Europeans of either community on one hand, and Africans and Indians on the other hand. By the mid- nineteenth century, the British were governing Natal and Cape Colony, while the people from Dutch origin created their own republics in Transvaal and Orange Free State. The Indians had arrived in South Africa originally as indentured laborers who were brought in to work in sugar plantations. Later, from 1870s onwards, a different set of Indians came, known as passenger Indians, who came on their own cost and free will and were largely engaged as traders and small shopkeepers. By 1876, there were an estimated 10,626 Indians in Natal alone. By 1891, Indians were almost as numerous as Europeans.

Mohandas Gandhi arrived in Durban on 24th May 1893. His first experience of racism was on a train on the way to Pretoria, the capital of Transvaal. He was booked on a first-class coach; however, after few stations, a railway official asked him to move to a third-class compartment. When Gandhi protested that he had a valid ticket, he and his luggage were thrown out of the train. Again, next evening when he took a stagecoach to move forward in his journey, the white coachman refused to let him sit inside, on the padded seats, even though Gandhi had a valid ticket. He had to dangerously hang on to the rails of the stagecoach. Gandhi even had difficulty in finding a hotel room because of his skin colour. These incidents left a deep impact on Gandhi. He later wrote, “the hardship to which I was subjected was superficial – only a symptom of the deeper disease of colour prejudice. I should try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process.” The malice of racism in South Africa also emerged from economic competiveness and insecurity of the white community vis-à-vis the Indians. Several Bills were in the pipeline which would make the life of Indians in Natal difficult and unprofitable. A Franchise bill, for example, would prohibit Indians from enrolling as voters. Natal had a history of many Act which encouraged discrimination of the Indians. One such Act was that Indians had to carry a pass when out in the streets at night. Traders were not permitted to sell on Sundays, the day when their main clients – Indian indentured laborers – were free. They were not allowed to open shops in the city centre also. These were some of the several handicaps imposed on Indians in Natal. It was an utter shock for Gandhi to confront such open racial prejudice against the Indians in South Africa. The newspapers were replete with derogatory remarks about the brown-skinned Indian, who is an “insanitary nuisance, and in no way can be considered as a desirable citizen”. It led to intense introspection by Gandhi who, through intellectual arguments against racism, aimed to devise a concrete plan of action to counter racial discrimination. Thus began the long drawn struggle led by Mohandas Gandhi. In this difficult and uncertain journey, Gandhi as a social and political agitator evolved. The path, however, which he chose was of passive resistance, rather than of violent protest. Gandhi along the way also got convinced that the struggle of the Indians needed widespread publicity and hence decided to start their own newspaper to represent the opinion of the Indians in order to reach out to the Europeans and the concerned authorities. This dream was brought to fruition in 1903. With the help of few Indians like Mansukhal Hiralal Nazar and Madanjit Vyavaharik, a journal, named Indian Opinion, was started. The first issue, appearing on 4th June 1903, announced itself as the voice of the Indian community.

“With a weak face, hesitant in court, polite in conversation, Mohandas Gandhi yet represented the first challenge to European domination in Natal.”

It is in South Africa that Gandhi developed his satyagraha (truth force) philosophy. Gandhi was kept tirelessly busy in his public work fighting peacefully for the Indian cause in South Africa. Gandhi was aiming for a compromise with the colonists through his proposals which would satisfy both the Indian community and the whites. It was during his stay in South Africa that Gandhi read ‘Unto this Last’, written by John Ruskin. He was so moved by the book that he could not sleep the whole night. The main takeaway from the book was that work of the farmers and laborers who worked with their hands was as valuable as that of lawyers, etc. It convinced him about the romance of an idyllic rural life. Gandhi was prompted to buy a farm which came to be known as Phoenix Farm, and the printing work of the journal was shifted there in 1904. The idea behind the farm was to lead a simple and natural life with minimal needs. Some years later, Gandhi acquired another farm and was further swayed by the allure of rural life.

When Gandhi read David Thoreau, he was influenced by his concept of civil disobedience. What Thoreau provided him was encouragement, not inspiration. “The settlements at Phoenix and Tolstoy were a meeting place, a melting pot, whereas the settlers lived and labored together, social and religious distinctions were mad irrelevant.” (Ramchandra Guha). Gandhi was both a practitioner and a theorist of satyagraha. Gandhi’s own belief in the power of passive, non-violent resistance was unshakable and solid.

South Africa was a learning experience for Gandhi, a lesson which he subsequently and successfully utilized and put into practice in India. There were several strands evolving and perfecting for Gandhi. He was an established lawyer, a political campaigner, a religious and moral explorer, a writer and a publicist. His views on passive resistance were given a new meaning by his concept of Satyagraha (truth force), which was a kind of civil disobedience based solidly on non-violence. Gandhi was also on the road to self-discovery, an endeavor at moral regeneration. Indian nationalist movement took a different and massive turn when Gandhi returned to India in 1915.