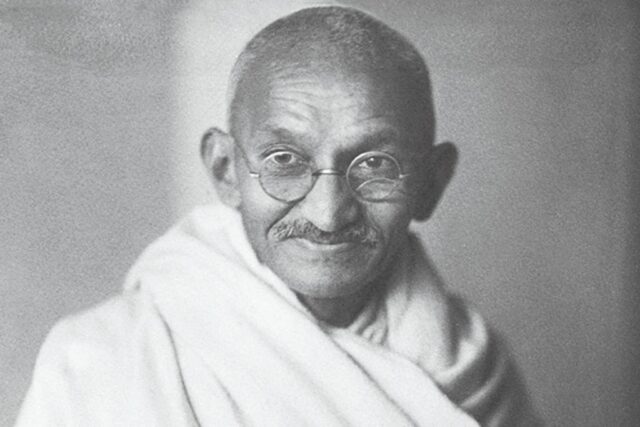

“India gave us a Mohandas, we gave them a Mahatma” goes a popular South African adage. Highlighting the transformative synergy that emerged from

M.K. Gandhi’s 21 years’ apprenticeship (1893-1914) in Natal and Transvaal, contemporary South African leaders, including Nelson Mandela,1 have eulogized him as being part of the epic battle to defeat the racist white regime. Integrated into the pantheon of South Africa’s heroes, Mandela even went as far as to assert that “India is Gandhi’s country of birth, South Africa his country of adoption. He was both an Indian and a South African citizen.”2

In the following short article, in homage to the Mahatma in the 150th anniversary of his birth, I shall briefly trace the metamorphosis of the mutual interaction and appreciation between Gandhi and South Africans, a dimension that has hitherto been inadequately studied in the narrative of the ‘Making of the Mahatma’.

Arriving in Durban, Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal) in May 18933, Gandhi came to serve as a legal counsel for a Gujarati Muslim merchant Dada Abdulla, originally for just one year, but was compelled to extend his sojourn to 21 years in order to fight against colonial injustice. It was this stay in South Africa which provided him with the tough apprenticeship that made him into a true satyagrahi. At several junctures, he could have given up, and gone home! The most well-known incident happened just ten days after his arrival, when, on the way to Pretoria in the service of his Muslim client, he was thrown off the train for presuming to sit in a first-class compartment for which he had a valid ticket. This personal affront precipitated ‘the most creative night of his life’, as he decided at the cold, mountain station of Pietermaritzburg to overcome his anger at this insulting treatment, and instead to turn his attention to the much larger

1 Former President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999; Mandela (18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was an eminent South African anti-apartheid revolutionary, political leader, and philanthropist.

2 Time Magazine, December 31st, 1999.

3 At the end of 19th century, Natal along with the Cape colony was under British rule, whereas Transvaal and the Orange Free State were held by the Dutch Boers. Indians arrived in South Africa in three waves: Between 1860 and 1911, about 150,000 South and North Indian (speaking mainly Tamil, Telugu, Bhojpuri and Awadhi) immigrants were brought to Natal as indentured labourers. From the mid-1870s entrepreneurs from Gujarat, the Konkan and Uttar Pradesh began arriving, to be followed in the 1890s by a third educated elite group (including lawyers, teachers, civil servants and accountants). Towards the end of the century, the extremely exploitative relationship between the white colonists (comprising about 10%-15% of the total population, numbering about 5 million) and the native African population (constituted of several different ethnic groups, representing at least 80% of the population) was being unsettled by enterprising Indians which inflamed racial hostility in particular towards Asiatics (amounting to about 5% of the total South African population); for more details, cf. William Kelleher Storey: Guns, Race and Power in Colonial South Africa. Cambridge 2008; and Zoe Laidlaw (ed.): Indigenous Communities and Settler Colonialism. Basingstoke 2015.

questions of racial prejudice (or the “disease of colour prejudice”4), injustice and exploitation directed against his fellow Indians in South Africa (numbering about 100,000) by the European colonists.

That the South African experience impacted on Gandhi’s conception of Indian identity and nationhood, and, on his understanding of colonialism, is well known. Even more crucially, it provided him with the ideal opportunity to develop his special technique of transforming society. But what role did Africans play in this saga? That Gandhi may initially have shared to a certain degree (albeit without any malice) the then all-pervasive racial prejudice cannot be completely ruled out. Yet, in this connection, Nelson Mandela, in 1995, made the following generously conciliatory observation:

“Gandhi must be forgiven those prejudices and judged in the context of the time and circumstances. We are looking here at the young Gandhi, still to become Mahatma, when he was without any human prejudice save that in favour of truth and justice.”5

Moreover, Gandhi was aware early on that the colonists’ race prejudice was directed against Indians and Africans, alike. Hence, he was instrumental in founding the Natal Indian Congress (NIC) on 22nd August 1894 which, though primarily aiming to protect the rights of Indians in South Africa, was subsequently to serve as an exemplary model for the African People’s Organisation (APO), established in 1902, and more significantly, the African National Congress (ANC), founded in 1912. As spokesman of the Indians, representing the NIC, Gandhi did in fact publically affirm that Africans should have voting rights:

“The Indians do not regret that capable natives can exercise the franchise. They would regret if it were otherwise. They, however, assert that they too, if capable, should have the right. You [i.e. the colonial administration], in your wisdom, would not allow the Indian or the native the precious privilege under any circumstances, because they have a dark skin.”6

By 1896 Gandhi had established himself as a political leader in South Africa. One of the first tasks that he took on was to oppose the system of importing indentured labour from India; the prime reason pointed out by Gandhi being that this system was detrimental to the interests of Africans. Consequently, India prohibited the export of labour to Natal in 1911.

When, in June 1904, Gandhi established a communal-living ashram called the Phoenix Settlement, the location he selected was at Inanda, in the rural surroundings outside of Durban, amid the local African population.

4 It is significant how, with this linguistic turn of phrase, Gandhi skilfully inverted the clichéd colonial categorization of Asians being backward and diseased.

5 Nelson Mandela: “Gandhi, The Prisoner” [A comparison of prison experiences and conditions of

Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela in South Africa], in: B. R. Nanda, ed., Mahatma Gandhi: 125 Years. New Delhi 1995, quoted from https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/speechnm1.htm.

6 Extract from an article by Gandhi, published in The Times of Natal, October 25th, 1894.

What is more, that Gandhi’s avant-garde alternative community was situated near the Ohlange Institution, the industrial school of John Langalibalele Dube7 is serendipitous to say the least. The interaction between the Phoenix Settlement and the Ohlange Institution was intense, with Dube and his students often visiting Gandhi’s ashram. More significantly, Dube’s weekly called Ilanga lase Natal was initially printed on the press of Indian Opinion (located at Phoenix). Gandhi himself often wrote in it about Dube; in particular, when reporting about a speech made by Dube, he underscored that the latter was an African “of whom one should know.”8 Prophetic words, for John Langalibalele Dube was to become the first President of the African National Congress.

Gandhi’s articles in Indian Opinion lauded other African leaders, too. More specifically, he commended the efforts of John Tengo Jabavu9 to raise the enormous sum of £ 50,000 from Africans for establishing a college for Africans. He wrote:

“[…] it is not to be wondered at that an awakening people, like the great native races of South Africa, are moved by something that has been described as being very much akin to religious fervour. […] British Indians in South Africa have much to learn from this example of self-sacrifice. If the natives of South Africa, with all their financial disabilities and social disadvantages, are capable of putting forth this local effort, is it not incumbent upon the British Indian community to take the lesson to heart, and press forward the matter of educational facilities with far greater energy and enthusiasm than have been used hitherto?”10

Gandhi, indeed, considered that his Indian compatriots could learn much from the fortitude and commitment of valiant Africans.

It was, however, the Bambatha Rebellion in 1906 that was to radically change the course of Gandhi’s life. The initial spark occurred when, Bambatha, a Zulu chief, refused to pay a new poll tax imposed on the Zulus. The tax was an onerous £ 1 on each adult when the average annual wage of an African was £ 5. In the ensuing discontent, a tax collector was killed, and a widespread rebellion followed. The Natal Government sent troops into the area and suppressed the rebellion after 4,000 Africans and 30 colonists were killed. Another 4,000 Africans were arrested and sentenced to brutal lashings. During the military operations of the Natal militia against Chief Bambatha and his followers, Gandhi organised a small stretcher-bearer corps of about 20 Indians. The corps, which served for a little over a month, was asked to take care of the wounded and whipped Africans since no colonial infirmary would treat them. Being

7 John Langalibalele Dube (11 February 1871 – 11 February 1946) was a South African essayist, philosopher, educator, politician, publisher, editor, novelist and poet.

8 Indian Opinion, September 2nd, 1905.

9 John Tengo Jabavu (11 January 1859 – 10 September 1921) was a political activist and the editor of Isigidimi samaXhosa, South Africa’s first newspaper to be written in Xhosa as early as 1876.

confronted at first hand with the colonial brutality against the Zulus was a traumatic experience for Gandhi. This is underscored explicitly by Nelson Mandela who articulated the following forcefully in an article:

“His [i.e. Gandhi’s] awakening came on the hilly terrain of the so-called Bambatha rebellion. […] British brutality against the Zulus roused his soul against violence as nothing had done before. He determined on that battlefield to wrest himself of all material attachments and devote himself completely and totally to eliminating violence and serving humanity.”11

Shaken to the core, Gandhi took a vow of celibacy and wrote to his brother that he had no interest in worldly possessions. A few months later to oppose the Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, or the humiliating ‘Black Act’, Gandhi mobilized the Indian community and highlighted the transformative power of nonviolence, manifested by Satyagraha, as a nonviolent force that has the potential to bring about conflict resolution vis-à-vis governmental injustice. A century later, in celebration of this event, Nelson Mandela proclaimed in February 2007:

“In a world driven by violence and strife, Gandhi’s message of peace and nonviolence holds the key to human survival in the 21st century. He rightly believed in the efficacy of pitting the soul force of the Satyagraha against the brute force of the oppressor and in effect converting the oppressor to the right and moral point.”12

During the subsequent struggle, Gandhi widened his horizon and publicly supported African rights. Also being appreciative about Africans, people of colour and whites showing solidarity13 and even going to prison with Indians, he formulated in an address to the YMCA, in Johannesburg, on 18th May 1908, his vision for a cosmopolitan South Africa:

“If we look into the future, is it not a heritage we have to leave to posterity that all the different races commingle and produce a civilisation that perhaps the world has not yet seen.”14

A couple of years later, whilst congratulating W.B. Rubusana15 on being elected to the Cape Provincial Council he, nonetheless, stringently criticized the continuing colonial restrictions:

11 Time Magazine, December 31st, 1999.

12 Cf. Nita Bhalla “Mandela calls for Gandhi’s non-violence approach”, Reuters, 29th January 2007: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-gandhi-mandela/mandela-calls-for-gandhis-non-violence-approach- idUSDEL34219720070129.

13 That this solidarity was reciprocal was underscored by Gandhi’s close companion, Hermann Kallenbach, as follows: “A black man may not use tramcars, so we walked together for miles. A black man may not use a hotel lift and bathroom, so both of us gladly left the use of both. A black man may not eat in the common dining room [so] I said I would not go there myself and we had our food in our rooms.” (Harijan, June 12th, 1937)

14 See Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG), 100 volumes, Delhi 1958-1994, vol. 8, p. 323.

“That Dr. Rubusana can sit in the Provincial Council but not in the Union Parliament is a glaring anomaly which must disappear if South Africans are to become a real nation in the near future.”16

Being greatly impressed by several educated Africans, Gandhi participated in discussions with them on the formation of a national body to defend African rights. Pixley ka Isaka Seme,17 who initiated the proposal, visited Gandhi in 1911 at Tolstoy Farm for consultation. The South African Native National Congress (later renamed the African National Congress) was formed in 1912 and was heralded by Gandhi as the “Awakening of Africa”.18 Yet, he never sought to impose his leadership over the African people, the “sons of the soil”, but presented them with the example of Satyagraha as a means of deliverance from oppression.

After returning to India in 1915, he kept up his interest in South Africa and often wrote about the oppression of Africans. During his visit to England for the 2nd Round Table Conference, in a speech at Oxford on October 24, 1931, he proclaimed:

“[…] as there has been an awakening in India, even so there will be an awakening in South Africa with its vastly richer resources – natural, mineral and human. The mighty English look like pygmies before the mighty races of Africa. They are noble savages after all, you will say. They are certainly noble, but no savages and in the course of a few years the Western nations may cease to find in Africa a dumping ground for their wares.”19

That India’s freedom must lead to Africa’s freedom was his firm conviction. Hence, as a source of inspiration, he received occasional visits from South African dignitaries, one of whom was Reverend S.S. Tema,20 a member of the ANC, who conducted an interview with Gandhi in his Sevagram Ashram.21 Since the content is quite enlightening, I shall refer to it in some detail: In answer to Rev. Tema’s first question as to how to make the ANC as successful as the INC, Gandhi responded with utmost frankness underscoring the need for the ANC members to be self-sacrificing and to adopt simple living. He elaborated as follows:

15 Mpilo Walter Benson Rubusana (21 March 1858 – 19 April 1936) was the co-founder of the Xhosa language newspaper publication, and the first Black person to be elected to the Cape Council in 1909.

16 Indian Opinion, September 24th, 1910.

17 Pixley ka Isaka Seme (c. 1881 – June 1951) was one of the first black lawyers in South Africa. He was born at

Inanda, close to Gandhi’s Phoenix settlement that he must have visited, especially since his mother was Dube’s sister.

18 Indian Opinion, February 10th, 1912.

19 See Rajeshwar Pandey: Gandhi and Modernisation. Delhi 1979.

20 He belonged to the Dutch Reformed Mission, Johannesburg, and had attended the International Missionary Council conference, held at Tambaram, near Chennai.

21 The interview was held on January 1st, 1939 and its text was published in Harijan, on February 18th, 1939, and reproduced in CWMG vol. 74, pp. 387-389.

“[…] while most of your leaders are Christians, the vast mass of the Bantus and Zulus are not Christians. You have adopted European dress and manners and have as a result become strangers in the midst of your own people. Politically, that is a disadvantage. It makes it difficult for you to reach the heart of the masses. You must not be afraid of being “Bantuised” or feel ashamed of carrying an assegai or of going about with only a tiny clout round your loins. A Zulu or a Bantu is a well-built man and need not be ashamed of showing his body. […] You must become Africans once more.”22

Not only did Gandhi stress the importance of simple authentic conduct, but also surprisingly discouraged Rev. Tema from forming an Indo-African front to confront the colonial administration, with the following elucidation:

“You will be pooling together not strength but weakness. You will best help one another by each standing on your own legs. The two cases are different. The Indians are a microscopic minority. They can never be a menace to the white population. You, on the other hand, are the sons of the soil who are being robbed of your inheritance. You are bound to resist that. Yours is a far bigger issue. It ought not to be mixed up with that of the Indian. This does not preclude the establishment of the friendliest relations between the two races. The Indians can cooperate with you in a number of ways. […] They may not put themselves in opposition to your legitimate aspirations or run you down as ‘savages’ while exalting themselves as cultured people in order to secure concessions for themselves at your expense.”23

In instilling self-assurance into Africans and upbraiding Indians for signs of cultural arrogance, Gandhi’s words ring true even today, and inspire us “to realise the basic unity of the human family [where] there is no room left for enmities and unhealthy competition.”24 And to highlight that his spirit still prevails and that Gandhi is appreciated by other African states, too, let me conclude by quoting his grandson Gopalkrishna Gandhi who stated:

“African leaders like Kenya’s Kenyatta, Nigeria’s Azikiwe, South Africa’s Luthuli and Mandela saw in Gandhi’s non-violent defiance of racism, an Asian’s quickening of a future African impetus for freedom.”25

Ela Gandhi (born 1 July 1940), granddaughter of Mahatma Gandhi (d.of Manilal), is a South African peace activist and was a Member of Parliament in South Africa from 1994 to 2004, where she aligned with the African National Congress (ANC) party representing the Phoenix area of Inanda in the KwaZulu- Natal province. Her parliamentary committee assignments included the Welfare, and Public Enterprises committees as well as the ad hoc committee on Surrogate Motherhood. She was an alternate member of the Justice Committee and served on Theme Committee 5 on Judiciary and Legal Systems.

22 Ibid., p. 388.

23 Ibid., p. 389.

24 Ibid.

25 Extract from an article by Gopalkrishna Gandhi in the Hindustan Times, December 18th, 2018.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of Diplomacy and Beyond Plus. The publication is not liable for the views expressed by authors.