The term Diaspora, like the condition it suggests, has been a constantly evolving one. What originated as a word to denote the scattering of Jews across continents, and was defined using a set of six features identified by Safran1 in the early days of its theorization, is today used in a larger, broader and more inclusive sense, and alludes to migrants, expatriates or exiles, as the case may be. Diasporic literature too is witness to such oscillations in definitions and includes the writings of immigrants and expatriates, besides exiles, and is increasingly beginning to accommodate writings about them too.

Any discussion on Indian literature, in general, requires one to consider writings in the various languages of the country; a discussion on Indian multilinguality and India diaspora literature is no exception to this. While Indian diasporic literature in English is now seen a category in itself due to its larger reach, writings in Indian regional languages are also being gradually sought by the reading public as well as scholars and academics. Writings of or on people of Indian origin who live in the U.K., the U.S., Canada, South Africa, Trinidad, Australia, Middle East and Far East, besides Europe, have made their mark in English and Indian languages in verse or prose, as poetry, fiction, drama, travel writing, and other non-fictional narratives.

Diasporic Writings: An Overview

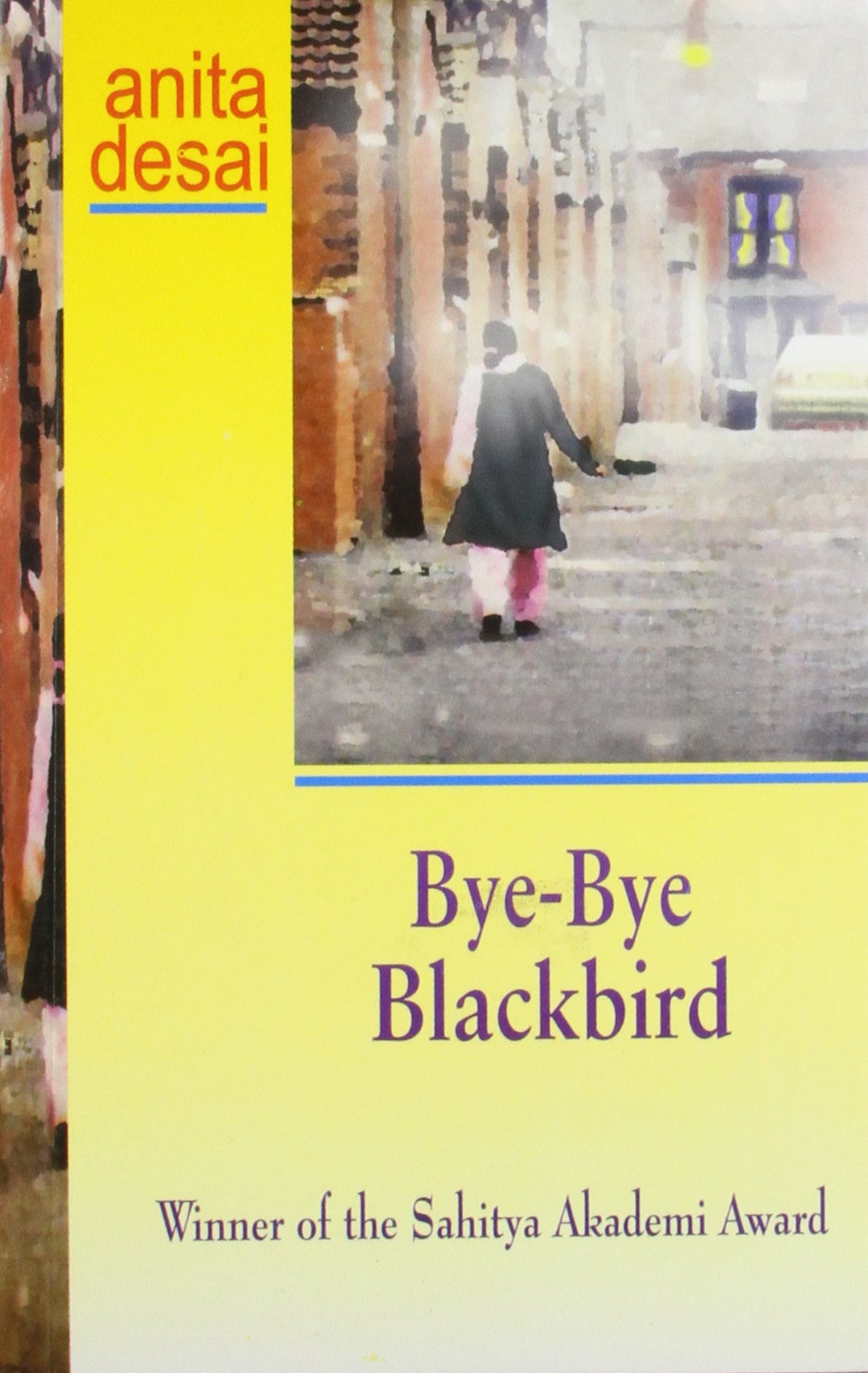

Migrancy, exile and other diasporic conditions have been significant topics of several Indian and Indian origin writers who write in English like Salman Rushdie, V.S. Naipaul, Vikram Seth, Amitav Ghosh, Anita Desai, Rohinton Mistry, Bharati Mukherjee, Meena Alexander, Jhumpa Lahiri, Chitra Divakaruni Banerjee, Sujata Bhatt, Hari Kunzru, Kirin Narayan, Anjali Joseph, Sanjay Nigam, to name a few.

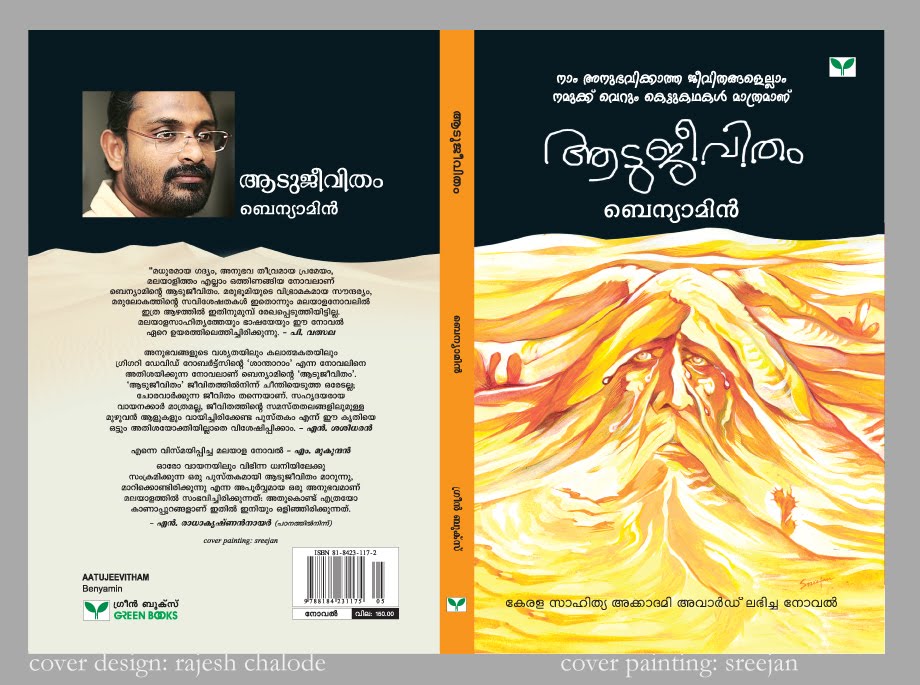

Similarly, diasporic elements can be found in regional writing too as heard in the voices of Hindi writers like Abhimanyu Unnuth, Manilal Doctor, Susham Bedi, Sudha Om Dhingra, Anita Kapoor, Abhinav Shukla, Satyendra Srivastava, Tejinder Sharma, Kavita Vachaknavi (Ref. RavindraKatyayan, epg book), Gujarati writers like Bhanushankar Oddhavji Vyas; Panna Naik (Pravesh, Videshini, Rang Jharukhe) [Ref. RajshreeTrivedi, epg book], Bengali writers like Ketaki Kushari Dyson (Jal Phunre Aagun or Fire Piercing Through Water, Tisidore) [Ref. Paromita Chakrabarti, epg book], Telugu writers like Chimmata Kamala’s (America Illaalu), Vanguri Chitten Raj (Amerikaalakshepam), America Telugu Kathanika, Ed. PemmaRajuVenugopalRao (Ref. Sireesha Telugu, epg pathshala), Malayalam writers like Benyamin (Aadujeevitham or Goat Days), Musafir Ahmed (Marubhumiyude Aatmakatha or The Story of a Desert), Shami (Nadavazhiyile Nerukal), and many others.

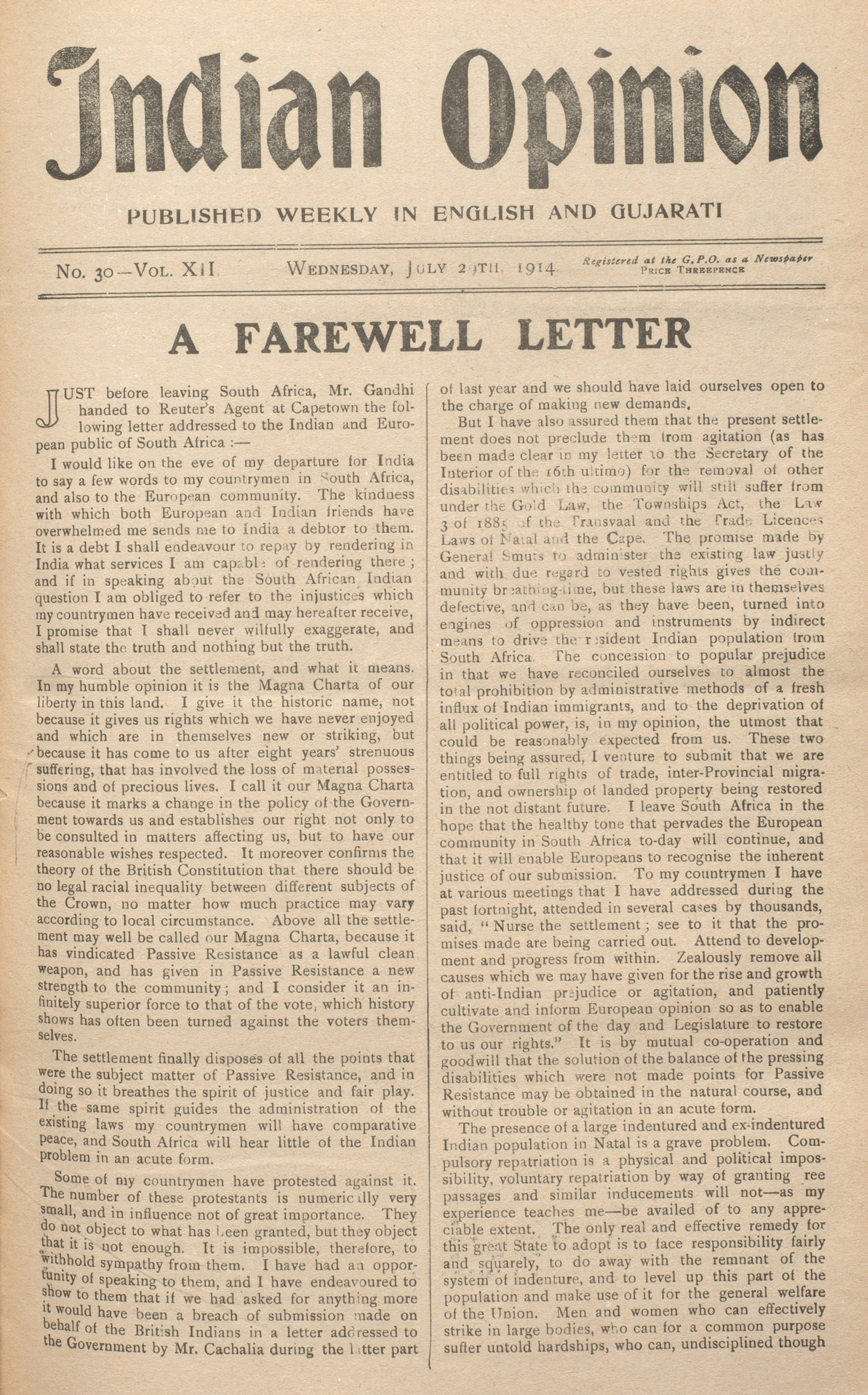

From Indian Opinion initiated by Mahatma Gandhi while in South Africa, to more recent Magazines like Agrobeej in Bengali, to blogs and other social media like the Indian diaspora dot com, other platforms have also opened up to give expression to the concerns of Indian diaspora.

Diasporic writings are often read from a lens of postcolonialism and categorized as Postcolonial writings, New Literature, South Asian Diasporic Writings and so on, albeit there exists a resistance to most such categorisations.

General Features, Themes and Concerns

Diasporic literature is, time and again, approached from the perspectives of nostalgia, loss and longing. While past and rootedness or rootlessness are often the central themes in many diasporic texts, they are not limited to such themes alone. They convey much more, and can even emerge as complementary readings to sociological studies on diaspora. From portraying culture shock and spatial shock, to examining minute details of identity politics, to illustrating generation gap to reverse culture shock and globalisation, diasporic literature juxtaposes the real and the imagined in a telling manner. Pithy stories of forced labour and migration and exile too find a space in diasporic writings, giving voice to a large group of people who otherwise lead a subaltern existence.

Linguistic concerns:

I ask you, what would you do

if you had two tongues in your mouth.

and lost the first one, the mother tongue,

and could not really know the other,

3

the foreign tongue.

You could not use them both together

even if you thought that way.

And if you lived in a place you had to

speak a foreign tongue,

your mother tongue would rot,

rot and die in your mouth

until you had to spit it out (Bhatt).

These lines form Sujata Bhatt’s ‘Brunizem’, where the dilemma of choosing one’s tongue is so delicately articulated, is echoed in a practical sense in Jhumpa Lahiri as “As long as there are ten finger and ten toe” in The Namesake, in the literal translation of the non-use of plurals in colloquial expressions, not unheard of in many Indian languages. While many of the works do not overanalyze the repercussions of such linguistic mishaps on account of mother tongue interference in the professional lives of the first generation immigrants, most of the texts do present situations in their personal lives, in their everyday transactions with a neighbor, or a shopkeeper, in the subway or in a café, and the raised eyebrows and the lack of understanding which translates into subconscious marginalization thereafter.

Race and colour:

As writings of and on a group that often exhibits a model minority image, contemporary Indian diasporic writings in English which portray the lives of high achieving groups like scientists, academics, medicos, techies and the like, have fewer instances of segregation in terms of race and colour. However, early writings in English as well as those which focus on the lives of the indentured labour groups, semi and unskilled migrants and expatriates, more pronounced in Indian vernacular writings, do confront issues related to race and colour more often than not. The lingering “I am not black, I am not black, I am grey” of Anita Desia’s Bye Bye Black Bird reflects the grey areas of identity construction: the Indian refusal to be accepted as black or brown and the British/western refusal to accept the so called fair as white, resulting in the grey identity, an in-betweenness which is neither black nor white, but the third space of hybridity, to borrow from Homi K. Bhabha. On a more serious tone, the racial segregation against the indentured Indian labour group is more persistently depicted in regional writings of early and recent times as in ManiLal Doctor’s Hindi works or in Benyamin’s Malayalam novel Aadujeevitham (Goat Days).

Identity:

Diasporic identity is generally read as a kind of fractured identity. While fragmentation, alienation, assimilation and sometimes acculturation are written all over a diasporic existence, and writings portray a great deal of hybrid and hyphenated identities, it goes without saying identity is in general not a constant, but an evolving process for everyone, as noted by scholars like Stuart Hall. However, such fluctuations in identity are accentuated by the diasporic condition and felt more by a migrant or exile or expatriate than by someone rooted to one’s home and homeland in the physical sense and this is captured sensitively in diasporic writings. As for the expatriates in Middle East, and other areas where the host country citizenship is denied and which record large scale labour movements with a mission to improve the socio-economic status of the families back home, the position of the “other” is felt in mixed proportions by the expats. Most literary representations here are however, concerned with the bleak, pitiable and near inhuman conditions of the unskilled and certain semi-skilled labourers who are often employed through illegal means than the comfortable lives of the highly skilled expats.

Nostalgia and loss:

Although these themes which bring in a constant association with the past are pronounced in most of these writings, the approach is different in different texts. While some look back with a true sense of nostalgia at the distant homeland, its traditions and culture, like Lahiri’s The Namesake, many also question such traditions and practices in the changed circumstances as in Bharati Mukherjee’s Jasmine or as in select stories in Divakaruni’s Arranged Marriage; the nostalgia and longing then being reserved only for lost bonds with family and friends and not for all kinds of traditions.

Generational conflict: Many diasporic texts like The Namesake show how home and homeland which haunt the first generation are mostly lost on the second generation and often questioned by them, and how the host land becomes home and homeland to the latter. However, we also get to see how at some point the second and the subsequent generations arrive at an understanding of the dilemmas of the diaspora when confronted with questions of race, colour and other issues in public spaces and in their personal and professional lives.

Spatial concerns: From experiencing a spatial shock on arriving at a new land to recreating home and homeland spaces, to mapping homeland and host land spaces, to addressing issues of transnational travel and migration to local commute, diasporic writings engage with spatial and territorial issues in multiple ways. Whether it’s the spatial practices of a Bengali homemaker in converting her domestic spaces to a socialized space through the Bengali

gatherings in The Namesake or the larger social space of a Little India Enclave as seen in Sanjay Nigam’s The Transplanted Man, the works also delineate the impact of migration in transforming spaces:

… Hindi film songs … blaring from stores with names like Raju’s Paan shop, Desi Dosa Palace, and Aaap Ka Dukaan, … Menus in restaurant windows advertised tandoori chicken, aloo chat, uttappams, and kulfis… With last night’s trash stuffed in bins up and down the Indian bazaar smells of spices and fried sweets, mixed with more disagreeable odors … Perhaps all that was needed was the sight of an autorikshaw belching black exhaust to dispel the sense of incongruity between place and smell. Whatever the reason, the smell wasn’t the same as the original, and it brought to mind all the things that were different (Nigam).

Globalisation and global citizen image: Often reverse culture and spatial shocks form a theme in diasporic works but in the globalized era, these texts are also increasingly moving from a pro-Indian, or pro-western or Indo-western identity to a more globalised identity. Although migration is defined as a journey without a clear return point by theorists like Hall, a return to the homeland on account of its changing façade in the wake of a different order of social, spatial, cultural and economic reality being gradually established through globalisation is not unnoticed by the writers as can be seen in Adiga’s White Tiger, Divakaruni’s One Amazing Thing, and so on.

Other subjects and themes:

Whether it is Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate and An Equal Music which are concerned with the lives of westerners, or Divakaruni’s retelling of myths in Palace of Illusions or her latest work Sita, or the speculative fiction of Anil Menon, other subjects are also explored from time to time.

Studies on diaspora are not entirely disengaged from diasporic literature which has informed the meticulous studies by scholars like Robin Cohen, Homi K. Bhabha, Stuart Hall, Edward Said, Vijay Mishra, James Clifford, Avtar Brah, Iain Chambers Ketu Katrak, Rajani Srikant and many more. Diasporic writings thus not only serve as an interactive archive of past, history and individual and collective memory, but also facilitate a rich database for understanding the identity politics, transnationalism, multiculturalism, and socio-spatial dialectics of our times.